New York state’s GlobalFoundries (GF) received news of $1.5 billion in direct funding and $1.6 billion in loans from the US Department of Commerce. The funds will be used to renovate fabrication facilities in Malta, NY (an hour’s drive from AIER’s campus in Great Barrington) and Essex Junction, VT, and to build a new Malta facility that will make chips for cars, planes, defense systems and artificial intelligence. Politicians and the chip industry claim government funding will spur an additional $12 billion investment from GF and create over 1,500 manufacturing jobs and roughly 9,000 construction jobs over the next decade. The deal has been praised by local state and federal officials as being a major boon to the economy of the region.

The investment promises to be a boon for GF and its employees in the short-run. But this latest example of government backing of American chipmaking offers an opportunity to weigh the benefits and costs of subsidies in our society at the local, national, and international level.

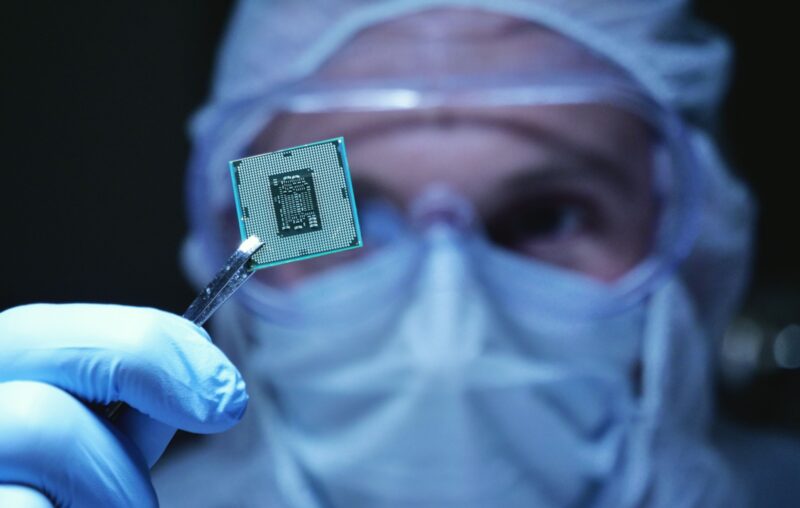

Funding for GF comes from the CHIPS Act, signed into law by President Biden in August 2022, which aims to make investments that strengthen American access to semiconductors, a crucial component in almost all electronic technologies used today. While New York state offered an additional $575 million in tax credits, the majority will come from the Department of Commerce. GF is the latest domestic chip manufacturer to receive subsidies from the slow rollout of CHIPS funding. GF is the third awardee, following Microchip Technology and BAE Systems, Inc.

In the short run, subsidized investments in companies like GlobalFoundries appear to reshore supply chains, create jobs, stimulate the economy, and secure American access to critical technology. But the positive short-run effects of the CHIPS Act and other forms of contemporary industrial policy risk distracting us from ensuring cooperative exchange and long-run prosperity in the global economy.

Arguments for these subsidies usually stem from concerns about the effects of supply shocks and geopolitical risks created by an assertive China. The pandemic alone caused a major disruption in the flow of semiconductors in the global economy. Disruptions of this kind can be devastating, because chips, as experts like Chris Millier observe, are the “new oil.” Because of this, a growing number of politicians, academics, and journalists call for investment in the industry to shore up national security and preserve advantages for American companies on the cutting edge of new developments in nanotechnology, clean energy, quantum computing, and AI.

With this massive amount of government support, GF will likely weather the uncertainty it faces in the marketplace. With the waning pandemic-era supply-chain woes, a slow down in tit-for-tat trade-war measures with China, and industry-wide growth on the horizon, firms like GF have a leg up on their non-subsidized competitors to reap the benefits of another boom in the silicon gold rush and claim a bigger share of the global market.

The honeypot of federal subsidies is sweet indeed. If you only listened to those pushing for the subsidy you might believe it’s all upside. But, for all GlobalFoundries promises to drive growth in cities like Albany, its place in the global semiconductor industry is all but certain. In fact, despite GF’s growth through the early 2020 to 2022, its share of global industry revenue actually declined by 1.7 percent over the same period. Despite new investments, and these subsidies, US chipmaker manufacturing capability will hover around a paltry 8 percent of global capacity for years to come. Real questions remain about whether GF’s promises of economic and job growth will actually occur. Meanwhile, the resources we allocate to chip production are diverted from all other possible voluntary, commercial opportunities.

On top of the uncertainties faced by firms life GF, reports suggest that a lion’s share of CHIPS funding will flow to Intel. As Intel engages in corporate jockeying for an additional $3.5 billion to create a “secure enclave” for the manufacturing of chips with highly sensitive technology. This constitutes an additional 10 percent of CHIPS funds — a plump cherry on top of the $10 billion Intel has all-but-secured. As economists and political scientists dating back to the 1970s argue, subsidies are rife with opportunities to already-giant firms, like Intel, to extract special privileges and “rents” from the government.

Small firms like GF will enjoy morsels, but legacy firms like Intel — who are already more immune to market shocks and decline — make subsidies into a buffet.

Industrial policy and investments in companies like GlobalFoundries might yield desirable effects in the short run. But subsidy programs often help the big get bigger. To wit, they are no substitute for serious thinking about how to guarantee economic prosperity in a globalized world where trade leads to prosperity. Indeed, as economic wisdom going back to Adam Smith dictates, the world is better off when we build open bazaars, not walled gardens.